What’s Beneath for Like The Wind issue #45

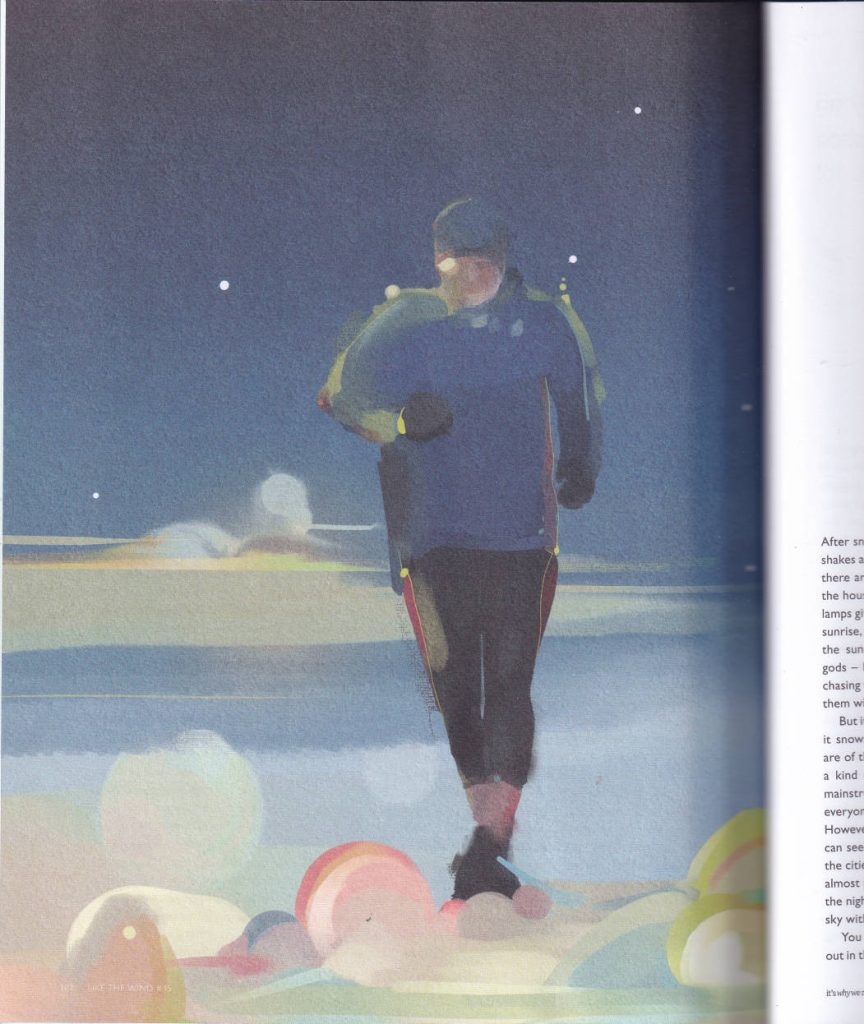

After snow, the skies glow different colours and the air shakes a little with the cold. At night and in the morning, there are thick pools of blackness that gather between the houses and under the cars. Dying light from sodium lamps gives everything a surreal glow. If you wake before sunrise, you can catch the dawn’s arrival and watch the sun take on the twilit, star-chased home of the gods – Nature’s forces dressed in sapphire and fuchsia chasing them away, dissolving the darkness and replacing them with light.

But it can take a while to see the world that way when it snows. Our first thoughts when the snowflakes fall are of things like snowballs, Christmas, sledges. There’s a kind of easy childishness, a surface projected from mainstream American films onto our streets, which everyone knows and understands – for a while at least. However, when it’s settled and laid across everything we can see, covering the fields, the houses, the valleys and the cities, there’s a sense of something older, something almost pagan that reaches north and up towards where the nights are longer and deeper and the sun shares the sky with the moon.

You can feel its arrival. It’s there in your desire to be out in the new landscape, in amongst the trees with their branches weighed down by snow, thinking about routes (and roots), dehydration and sunglasses. Which parts of my world are beneath the snow now? Time gets thicker and black ice creeps into all travel plans.

Frankly, the words for all this escape me, but it’s where I’m at when I get up at 6am, the house encased in a freezing white winter, to travel to Tony’s. I drive like it’s my first time in a car along snowy roads with footprints down the centre. Our goal: a run up Derwent Edge in the Peak District National Park.

I pass plenty of hills and don’t trust them in the snow. The main roads are fine though and I arrive a little late and tense, but safe. Tony gets into my car and we drive as the blue in the sky gets deeper and a sunrise bursts overhead. Jobs, money and time disappear and are replaced by an apricot glow behind the hills. The world is all distance, pace and light.

Now we’re at Cutthroat Bridge and in the freezing air. Now we’re running slowly in the half-dark, running past one or two other cars, down the side of the road and up towards where the path should be. It’s there, but hidden under snow, and another runner – a woman who passes us – says hello and is gone into the shimmering distance, heading north. We crunch and wend in the direction of Derwent Edge and watch the light from behind the hills spill from the sky across the snowfields.

The snow kills our sense of distance and in its place grows the desire to keep moving, to stay out of the shadows, to stay warm and to get a grip on the new topography that came down in the night. As sunrise stakes a claim to the earth, my breath feels like it’s close to my ears. There’s a muffled sensation that comes with running in the freezing snow and ice. Each crunching footstep feels like it only makes it as far as our ears and no further. We’re the only people for miles around. In a small, shadowed valley the hills around us look like blue triangles piled on top of each other, getting smaller and bluer the higher they go. There are tracks ahead and it’s easy to see the path we need to take to get up high and into the sun.

Vapour piles above us in the air wherever it can. Our breath billows like shower steam and on the horizon gather small clouds the shape of water boiling, their tips pointing upward, eastward and north. Further up the ascent and away in the distance, I can see the expulsion from a power station’s steam turbine, shaped like a flamethrower jet and flat as an anvil on top – perhaps because the jet has hit air so cold it can go no further. It looks strange and it sticks in the mind; a picture to carry along with me, like the plants encased in finger-thick ice, the twirling frozen shapes with the old world inside them, and the vision-killing tip of sunlight breaking over the triangular hills, announcing the arrival of the day.

For some reason, when we look at something small we see echoes of what’s big, but we don’t see echoes of what’s small in big things. When I look at the ice crystals and the frost – on the ground and wrapped around plants and trees – I can see little cities and mountains. But when I venture into a city, I don’t see tiny plants blown up to the size of skyscrapers or houses that look like boulders. I don’t know why this is, but as I’m wondering and running, I see that maybe I’m wrong. There’s a rocky outcrop that looks like horse dung, but as we get closer it starts to look like a pile of clouds or UFOs and as we get closer still, it towers over us and it begins to look like it’s made from the human-organ shapes in an HR Giger painting. The wind and rain make beautiful things sometimes.

The world we’re running through feels like it’s from a north that exists beneath our thoughts. It’s tied to pine forests, meadows of snow and funerals that include fire. When I die, I expect that someone will wonder how to send me off, how to do some sort of justice to my life and writing and artwork. They’ll probably look through my heritage and comb through the Polish side of my family, looking for funeral rites and interesting things to do and say about my time on Earth. Or they might go through the Irish side and try to find something mythical there. If you’re reading this, looking for something to use at my funeral, then my guess is you’ve come up with nothing except a big bonfire of my records, my running shoes (not entirely unreasonable actually) and my books. Do not do this. Don’t throw me on a fire. Instead, think about the world under the snow, the one from the north, and just sit with it for a while.

Every night, the cat snores at the foot of the bed and this makes me feel somehow comfortable and connected to the universe. The rocky outcrops we’re running past make me feel a similar way, but through shape rather than sound. The next outcrop is called the Cakes of Bread and it looks like someone is camping there – I can see what looks like a tent on the horizon. There’s over a mile of bright, white snowfield between us; the hard-to-define old/new ice world on top of the previous one, made of roles and time and computers.

Now we’re on the Edge proper, we get a steady rhythm going. It’s been hard to do that until now, mainly because the snow is deep and frozen and has its own topography – and because it’s easy to break through the snow, drop two feet and find yourself standing on the hard earth below. I cut my shin doing this and it’s more painful than I expect. The red blood makes me think of plasters and bandages and my thoughts sink back to work things, hobbling to the shops and back and arranging my trousers so they don’t become stained. The temperature is about -4°C and it stays that way until we get back to the car some three hours later.

The idea of a real world beneath this one, a simplified world where people run free in Nature, is probably just as manufactured as the Christmas-snowballs-and-silly-films nexus and likely from advertising too. I’m not a salesman, but if I were to sell anything, I would try to sell people their own selves – complete with all the ugliness, pain and joy. And I would do it for free. But no amount of money changing hands will give you who you are. It’s something you have to go and do yourself, on your own and with mistakes, out somewhere away from it all and mixed in with everyone and everything else, in whatever time you can spare.

Up around the Cakes of Bread, we get to the man who camped in the open snow overnight. He looks peaceful and he nods quickly as we pass. Everyone can see and feel how beautiful the sun on the snow is and it seems a shame to distract anyone for too long from it. It’s so cold that the edges of everything seem blurred. Taking our gloves off – even for a minute – makes the tips of our fingers hurt. The blues that come from the cold are a special kind of blue that I never see at any other time. Maybe the azures seem so flinty because they gradate into mauve, apricot or pink. They’re intense, fascinating – gargantuan. Tony and I take lots of photographs.

There are more runners than I expected; fell runners obviously know to come here for the sunrise when it’s been snowing. Tony falls a few times, a victim of the snow’s redesign of the land, his feet plunging through the smooth, frozen hummocks into the dark depths beneath them, the spell of the far north broken briefly each time. We stop for a moment near some plants so caked in ice they look like crystal cauliflowers.

The sun has risen and we stop briefly at each outcrop. Snowfields and ice sheets have overwritten Derwent Edge, and the closer we get to Lostlad the fewer footprints there are. We see a few more runners and a couple with dogs. The dogs are the embodiment of joy in the snow, no matter how deep it is for them. They leap and twist in the air, getting as high as they can before falling back, disappearing into it, chewing it and shaking their heads and tails. Everyone we pass seems happy.

At Lostlad, my shin is bleeding too, as well as my ankle. The cold makes it hurt more for some reason. Tony has injured his ankle and we decide this is far as we will go. Both of us are happy we’ll be running slightly downhill on the return leg. This section is the same as a portion of the Nine Edges, but it’s unrecognisable. Kinder is visible, white as we are; below us, Howden is black and ringed with pine forest, dark and smudged in the cold.

The sun is high and bright now, like an interrogation lamp, but it’s too cold to be out here for much longer. We run down into the valley and the temperature drops even further, mist rising around us and ice becoming more common. Tony reminds me that valley floors are often colder than the top of their sides. And as the road comes into view, what’s beneath suddenly seems more real and the delicate layers that came down with the snow seem thinner and more worn, the earth beneath reasserting itself. What’s underneath wants us to return.

We get back to the car and the car park is full. A man from Nottingham wants our space. He waits patiently and chats while we shiver, remove our steaming socks and shoes, scramble into the car to drink some ice-cold water and put the heater on. Twenty-five minutes later, I’m home and answering emails.

This piece originally appeared in Like The Wind Issue 45.